Ultimamente sui gruppi di discussione americani che frequento sono comparsi molti articoli tratti dalla stampa USA a proposito degli ascolti radiofonici in calo e della faticosa, problematica (forse condannata all'insuccesso) affermazione della radio digitale HD. Roba abbastanza deprimente che non volevo nemmeno pubblicare. Stamane chattando con Andrea Borgnino sono venuto a sapere che Repubblica (a proposito, speriamo che con Daniele Mastrogiacomo finisca tutto bene) ha pubblicato proprio uno degli articoli che avevo letto sul suo supplemento realizzato insieme al New York Times, dedicato alla lenta trasformazione di alcune stazioni in direzione del Webcasting video. Ma la radio in tv, pur sempre via Web, è ancora radio? Se volete la traduzione la trovate a pagina cinque di

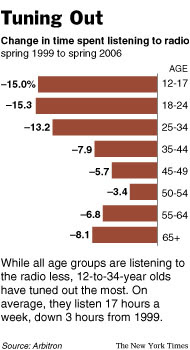

questo supplemento, altrimenti potete leggere la storia di RIchard Siklos - dedicata alle strategie Internet di molte stazioni - qui nell'originale, insieme a un articolo dello stesso autore che analizza la significativa erosione di ascolti delle stazioni radiofoniche, soprattutto musicali (sono in crescita invece i formati di notizie e approfondimento, chissà che qualcuno dei programmisti che inondando l'etere nostrano di canzonette sceme e show radiofonici di pessimo gusto non se ne accorga...)

Is Radio Still Radio if There’s Video?

By RICHARD SIKLOS February 14, 2007

(http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/14/business/media/14radio.html?ex=1173416400&en=d023f1fd8fde6e5a&ei=5070)

Ted Stryker, a D.J. at KROQ in Los Angeles, considers it a perk of the job to wear shorts and T-shirts to work. But last Sunday as he dressed for the Grammy Awards, he pulled out his best blazer and a flashy belt buckle, knowing three video cameras would stream live coverage of his show to the Web sites of 147 CBS radio stations.

Ted Stryker, a D.J. at KROQ in Los Angeles, considers it a perk of the job to wear shorts and T-shirts to work. But last Sunday as he dressed for the Grammy Awards, he pulled out his best blazer and a flashy belt buckle, knowing three video cameras would stream live coverage of his show to the Web sites of 147 CBS radio stations.

“What’s great about radio is no one knows what you’re wearing,” Mr. Stryker said by telephone as he made his way through the throng at the Grammys. “I wanted to make myself a little bit more presentable.” Mr. Stryker, who has done some TV work in the past, said that to create his best radio voice, he often must contort his face in embarrassing ways.

“It’s so different doing radio compared to TV,” he said. “Who knows what faces I make when I’m talking on the radio? I hope I’m not making the same faces today.” The nation’s commercial radio stations have seen the future, and it is in, of all things, video. As a result, the stereotype of a silken-voiced jockey like Mr. Stryker, slumped and disheveled in the studio chair, may never be the same.

Across the country, radio stations are putting up video fare on their Web sites, ranging from a simple camera in the broadcast booth to exclusive coverage of events like the Super Bowl to music videos, news clips and Web-only musical performances.

“This is no longer the age of ‘having a face for radio,’ ” said Dianna Jason, the senior director of marketing and promotions at Power 106, a Los Angeles hip-hop radio station. “This is a visual medium now.” Audiences in Los Angeles, for example, will be able to tune in today to Power 106 for an annual Valentine’s Day event called “Trash Your Ex,” in which jilted listeners are invited to put mementos from past loves in a giant wood chipper — and to let it whir while the disc jockey, Big Boy, urges them on. And for the first time, audiences everywhere will be able to watch streamed video of the event, to be held in a parking lot in Pasadena, on the Web site power106.com.

Whereas video was once said to have killed the radio star — according to the pop song by the Buggles that was the first video shown on MTV in 1981 — it is now emerging as an unlikely savior for an industry facing an array of challenges. In the age of YouTube and the radio talk show hosts Howard Stern and Don Imus as television stalwarts, this might not seem all that remarkable, except that the radio industry has been singularly tardy in embracing the interactive age. But now many of the largest radio companies are scrambling to stay relevant as their listeners’ attention is drawn in many directions — iPods, cellphones, satellite radio and various streaming and downloading musical offerings from companies like Yahoo and AOL. “A lot of our stations are starting to embrace video and generate new revenue streams,” said Joel Hollander, the chief executive of CBS Radio, the nation’s second-largest radio company, after Clear Channel Communications. “I hope video helps the radio star. Maybe radio will save the video star?”

More than 90 percent of Americans still listen to traditional radio. But the amount of time they tune in over the course of a week has fallen by 14 percent over the last decade, according to Arbitron ratings. Industry revenues are flat, and the Bloomberg index of radio stocks is down some 40 percent over the last three years. Reflecting the investor malaise, a group of private equity companies has proposed buying Clear Channel Communications and taking it private. Video now makes up only a tiny fraction of the $20 billion a year that radio generates in advertising sales. But it could represent a much-needed new source of growth in a rapidly expanding online video market that everyone from Google to newspapers to broadcast television wants to be in.

Radio executives and personalities say their video efforts will be different because they capitalize on radio’s traditional strength in using on-air personalities and local events to draw in listeners. Taking a cue from YouTube and the rise of user-generated video, a polished, TV-quality product is often not the objective. Another Power 106 video effort featured a staff member, dressed like a shrub, jumping out of a planter to surprise visitors to the station’s office on Halloween. An alternative rock station, 94.7 FM in Portland, Ore., last fall began a “Bootleg Video” series in which a listener is lent a video camera to record a clip of a local performance by a hot band like the Killers for the Web site. “Sometimes it’s a little shaky, but we want that,” said Mark Hamilton, manager at the station, which is owned by Entercom Communications. “We don’t want it to be perfect.”

The Web site for the radio station WFLZ in Tampa, Fla., features a video series called “Naked,” on the lives of its hosts away from the microphone. “I’m not very pretty today,” one of the station’s disc jockeys, Ashlee Reid, says sheepishly on the latest installment as she arrives at work and realizes the cameras are rolling before bantering with a colleague about chest hair.

Ms. Reid, who is 26, said being videotaped was odd, but in the year that the radio station has been producing monthly installments of the show for downloading, it has not yet caused her and her colleagues to alter their hair or wardrobe. “Maybe we should, but we don’t,” she said.

Similarly, producers for Adam Carolla, the Los Angeles morning host whose program is carried on many CBS Radio stations, regularly record vérité clips featuring Mr. Carolla and a co-host, Danny Bonaduce, for posting on the Web.

The nation’s biggest radio companies are also doing slicker productions, like Mr. Stryker’s Grammy show, that try to capitalize on their size and reach. Clear Channel, whose Internet efforts are led by Evan Harrison, an executive vice president, has elaborate video programming available on the Web sites of its 1,200 stations, including Tampa’s 933FLZ.com, where “Naked” is featured. Clear Channel has made some 6,000 music videos available for downloading online, but has also been producing original video content that individual stations can feature on their Web sites and disc jockeys can promote on the air. These programs include “Stripped,” a series of taped performances by artists like Young Jeezy and Nelly Furtado that are often acoustic or done in small clubs. The company has also been producing “Video 6 Pack” in which bands like Fall Out Boy appear as hosts of their own program and play videos they like.

According to comScore Media Metrix, Clear Channel sites ranked sixth in December among music Web sites, behind MTV, AOL, Yahoo, MySpace and Artistdirect.

Radio industry executives stressed that, so far, their video efforts could be considered experimental and only one facet — along with blogs and audio podcasts and a nascent service called HD Radio — of how the industry is adapting for the Internet age. “People are either going to have to get with the program or get lost,” Fatman Scoop, a disc jockey on Hot 97, an FM station in New York, said in an interview. “People don’t sit in front of a radio for three hours like they used to. If they don’t hear a song they like, they go to the Internet.”

In his case, what listeners will find on hot97.com is a weekly video show about relationships that Fatman produces with his wife, Shanda Freeman, called “Man and Wife.” Introduced in November, the shows are usually taped in the couple’s bedroom in New Jersey and run several minutes each. Fatman, who prefers to be known by his radio name, said that the show was entirely owned by him but that his bosses at Hot 97 — owned by Emmis Communications, like Power 106 — recognize that raising the visibility of its personalities on the Internet could only be good for attracting listeners and advertisers.

“What we’re trying to do is reach the listener in any way possible,” he said. “If somebody sees that you’re on ‘Man and Wife’ on hot97.com, they will listen to your show.”

Radio and video may be a more natural fit than expected. In his book “Understanding Media,” the cultural theorist Marshall McLuhan wrote that “the effect of radio is visual.”

Certainly, Howard Stern and Don Imus have had video extensions of their radio shows for years. Even Mr. Stern’s new employer, Sirius Satellite Radio, is planning a move in that direction. The company has said it plans to start beaming a video service of children’s programming to play on screens in the cars of Sirius subscribers sometime this year.

For now, most of the new video ventures originating from radio are just starting to generate revenue. Mr. Hollander of CBS Radio and Mr. Harrison of Clear Channel declined to say how much new revenue they were attracting.

Mr. Hollander said plans were in the works at the CBS Corporation, which is better known for its television network, to begin integrating some of its video programming into the radio division’s Web sites. The Web site for WSCR, the company’s sports radio station in Chicago, featured live video from its pregame coverage of the Super Bowl in Miami. Earlier, the station streamed coverage of its 15th-anniversary celebration.

Mitch Rosen, the station manager for WSCR, said the video efforts attracted advertisements from 8 to 10 businesses that normally thought of the station as only an audio outlet. To add some visual flair to the anniversary broadcast, Mr. Rosen put two of the station’s popular hosts in tuxedos. “They did get some ribbing from listeners,” Mr. Rosen said.

For crossover advocates like Fatman, however, audio and video will soon be interchangeable in the D.J.’s repertory. “That’s where it’s going,” he said. “It’s getting to the point where you’re going to have to be good at both.”

Changing Its Tune

By RICHARD SIKLOS September 15, 2006

(http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/15/business/media/15radio.html?ex=1173416400&en=670d7b77afabafd3&ei=5070)

The radio industry keeps losing people like Danny C. Costa, a senior at Boston University who grew up listening to radio in New York and New Jersey. For the last few years, Mr. Costa has tuned out radio in favor of Web sites where he can get access to downloads or videos he heard about from friends. He prefers these to the drumbeat of the Top 40. He burns his favorite songs onto CD’s or copies them onto his iPod. “I just sort of stopped listening to radio, because I had access to all this music online,” Mr. Costa said. While more than 9 out of 10 Americans still listen to traditional radio each week, they are listening less. And the industry is having to confront many challenges like those that have enticed Mr. Costa, including streaming audio, podcasting, iPods and Howard Stern on satellite radio.

University who grew up listening to radio in New York and New Jersey. For the last few years, Mr. Costa has tuned out radio in favor of Web sites where he can get access to downloads or videos he heard about from friends. He prefers these to the drumbeat of the Top 40. He burns his favorite songs onto CD’s or copies them onto his iPod. “I just sort of stopped listening to radio, because I had access to all this music online,” Mr. Costa said. While more than 9 out of 10 Americans still listen to traditional radio each week, they are listening less. And the industry is having to confront many challenges like those that have enticed Mr. Costa, including streaming audio, podcasting, iPods and Howard Stern on satellite radio.

As a result, the prospects of radio companies have dimmed significantly since the late 1990’s, when broadcast barons were tripping over themselves to buy more stations. Radio revenue growth has stagnated and the number of listeners is dropping. The amount of time people tune into radio over the course of a week has fallen by 14 percent over the last decade, according to Arbitron ratings. Over the last three years, the stocks of the five largest publicly traded radio companies are down between 30 percent and 60 percent as investors wonder when the industry will bottom out. Now, radio’s woes have spurred a new wave of deal making.

Clear Channel Communications, the nation’s largest radio operator, is now considering selling some of its 1,200 stations in smaller markets after years of acquiring everything in sight, according to industry analysts. The Corporation">CBS Corporation did the same thing recently and now says it is looking at further station sales. The Walt Disney Company struck a deal this summer to get out of the radio business altogether, and in May, Susquehanna Broadcasting, the nation’s largest privately held radio group, was sold to another broadcaster.

But rewriting the ownership map is just part of radio’s scramble to find a new groove. In the last year, the industry has moved into overdrive by increasing experimentation with new formats and starting digital initiatives like HD Radio — a nascent format that will allow listeners with special tuners to hear more specialized channels. Radio companies are moving fast into Web businesses that incorporate video and other features that could not have been imagined when commercial radio first appeared nearly nine decades ago. “It’s not a debate any more that radio is a structurally declining sector,” said Michael Nathanson, media analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Company. “What you’re starting to see are strategic changes in operating models to address the sluggishness of growth.” What has set radio apart from other challenged media businesses — like video rentals, magazines, television stations and newspapers — was the swiftness of its fall from grace on Wall Street.

A possible reason is that unlike other media businesses, radio appears to have come late to the game of focusing on viable online business models. Although digital revenues are growing fast, they accounted for only $87 million of the industry’s $20 billion in 2005 revenues, according to Veronis Suhler Stevenson Communications. It is not just students in their dorms who are spending their listening time elsewhere. Larry R. Glassman, a surgeon who does lung transplants and commutes between Cold Spring Harbor and Manhasset, N.Y., each day, used to tune into radio for his 40-minute drive, particularly to hear his classic rock favorites.

But now he subscribes to XM Radio, and recently had an XM receiver installed in a new boat. “Some of the programming I just flip over,” he said, adding that he would listen to XM in surgery if he could. Instead, “I use the iPod in the operating room.” Mr. Glassman, who is 51, said he turned a deaf ear to radio primarily because of the advertising and because he finds the playlists of his favorite stations too mainstream and limited. Broadcast radio advertising over all was up 0.3 percent in 2005, lagging in growth in comparison with the gross domestic product for the third consecutive year. It will continue to lag economic growth for the next five years, according to Veronis Suhler. (Only the newspaper industry gets a slower top-line growth prognosis.)

Radio’s digital efforts come as the nation’s two satellite radio companies — XM and Sirius — have amassed more than 11 million subscribers drawn to the services’ marquee names, led by Mr. Stern and various sports leagues, niche programming, sound quality and fewer or no advertisements. Still, some broadcasters argue that satellite has grabbed an unfair share of buzz given that its audience subscribers pale beside the roughly 230 million Americans who listen to old-fashioned free radio. “As an industry, we’ve lost the hipness battle,” said Jeffrey H. Smulyan, the chief executive of Emmis Broadcasting. “Like a lot in life, it may be more perception than reality.” (Mr. Smulyan tried to take his company private earlier this summer in the face of its sagging stock price, down more than 40 percent since 2003.)

But the radio companies are looking to fight back with innovations of their own.

Clear Channel, for instance, signed a deal with BMW earlier this month to provide real-time free traffic updates to navigation systems in the automaker’s new models. The company announced another deal to beam its radio signals to Cingular wireless phone users, offering them streaming and on-demand content as well. “We’re going to go to all sorts of different distribution platforms and have an additional five, six or seven revenue streams that we didn’t have even 24 months ago,” Mark P. Mays, Clear Channel’s chief executive, said in a recent interview.

Clear Channel has already tried other things — including stock buybacks, spinning off its outdoor advertising division and hiring a senior executive from AOL to oversee its online music efforts. It also adopted a much-watched plan to reduce on-air clutter by reducing the amount of advertising it broadcasts and running shorter spots.

Clear Channel managed to outperform the industry in its latest quarter, increasing revenue by 6 percent. In aggressively moving online, radio companies are starting to offer new services with the sort of personalization that appeals to Web-savvy listeners. And they have put a greater emphasis on unique local programming — news, sports, traffic, weather and talk — that is tough for Web competitors to emulate. Clear Channel already has one of the most visited music sites on the Web, and CBS Radio, formerly known as Infinity Broadcasting, has aggressively stepped up an Internet presence that was nearly nonexistent since last year. The company now streams more than 70 of its stations live, and it has started KYOURadio.com, a kind of a YouTube.com for listener-generated Podcasts.

The company has flipped formats at 27 of its stations since last year, pursuing growing areas like Spanish-language radio and using the popular Jack format, which has no on-air host and evokes the randomness of surfing for popular music. In the first six months of the year, the operating income of CBS’s radio business fell 17 percent. Joel Hollander, chief executive of CBS Radio, said in an interview that although the business was not growing as it once did, it generated a lot of cash for the CBS Corporation and required relatively little capital investment. “This is still a fabulous business,” he said. Mr. Smulyan said he hoped that HD Radio and radio stations’ budding presence on the Web could help restore the luster of the business. Peter L. Supino, an equity analyst at Wallace R. Weitz in Omaha, said the radio industry had awakened to the need to revamp the way it sold advertising and focus on improving its product, both online and off. “It seems like an industry that had a nice run in the 1990’s that didn’t have to worry — it was just ‘step on the gas and take more in sales every year,’ ” said Mr. Supino, whose firm holds shares in Cumulus Media, the radio company.

While radio companies are pinning their hopes on HD Radio, it is still at least three years from becoming a big enough business to have an impact on industry revenues. And John S. Rose, a partner in the media practice at the Boston Consulting Group, says the industry has not yet figured out ways to use the pristine sound quality of HD Radio to offer paid downloads of songs.

Amid so much uncertainty, it is little wonder that sessions at next week’s National Association of Broadcasters radio convention in Dallas advertise things like: “Learn to steal money from your local newspaper” and “Harnessing the power of blogging.” It is also a sign of the times that the convention’s opening reception does not have a broadcaster as a host. Instead, Google will be buying the drinks.

Ultimamente sui gruppi di discussione americani che frequento sono comparsi molti articoli tratti dalla stampa USA a proposito degli ascolti radiofonici in calo e della faticosa, problematica (forse condannata all'insuccesso) affermazione della radio digitale HD. Roba abbastanza deprimente che non volevo nemmeno pubblicare. Stamane chattando con Andrea Borgnino sono venuto a sapere che Repubblica (a proposito, speriamo che con Daniele Mastrogiacomo finisca tutto bene) ha pubblicato proprio uno degli articoli che avevo letto sul suo supplemento realizzato insieme al New York Times, dedicato alla lenta trasformazione di alcune stazioni in direzione del Webcasting video. Ma la radio in tv, pur sempre via Web, è ancora radio? Se volete la traduzione la trovate a pagina cinque di questo supplemento, altrimenti potete leggere la storia di RIchard Siklos - dedicata alle strategie Internet di molte stazioni - qui nell'originale, insieme a un articolo dello stesso autore che analizza la significativa erosione di ascolti delle stazioni radiofoniche, soprattutto musicali (sono in crescita invece i formati di notizie e approfondimento, chissà che qualcuno dei programmisti che inondando l'etere nostrano di canzonette sceme e show radiofonici di pessimo gusto non se ne accorga...)

Ultimamente sui gruppi di discussione americani che frequento sono comparsi molti articoli tratti dalla stampa USA a proposito degli ascolti radiofonici in calo e della faticosa, problematica (forse condannata all'insuccesso) affermazione della radio digitale HD. Roba abbastanza deprimente che non volevo nemmeno pubblicare. Stamane chattando con Andrea Borgnino sono venuto a sapere che Repubblica (a proposito, speriamo che con Daniele Mastrogiacomo finisca tutto bene) ha pubblicato proprio uno degli articoli che avevo letto sul suo supplemento realizzato insieme al New York Times, dedicato alla lenta trasformazione di alcune stazioni in direzione del Webcasting video. Ma la radio in tv, pur sempre via Web, è ancora radio? Se volete la traduzione la trovate a pagina cinque di questo supplemento, altrimenti potete leggere la storia di RIchard Siklos - dedicata alle strategie Internet di molte stazioni - qui nell'originale, insieme a un articolo dello stesso autore che analizza la significativa erosione di ascolti delle stazioni radiofoniche, soprattutto musicali (sono in crescita invece i formati di notizie e approfondimento, chissà che qualcuno dei programmisti che inondando l'etere nostrano di canzonette sceme e show radiofonici di pessimo gusto non se ne accorga...)Ted Stryker, a D.J. at KROQ in Los Angeles, considers it a perk of the job to wear shorts and T-shirts to work. But last Sunday as he dressed for the Grammy Awards, he pulled out his best blazer and a flashy belt buckle, knowing three video cameras would stream live coverage of his show to the Web sites of 147 CBS radio stations.

University who grew up listening to radio in New York and New Jersey. For the last few years, Mr. Costa has tuned out radio in favor of Web sites where he can get access to downloads or videos he heard about from friends. He prefers these to the drumbeat of the Top 40. He burns his favorite songs onto CD’s or copies them onto his iPod. “I just sort of stopped listening to radio, because I had access to all this music online,” Mr. Costa said. While more than 9 out of 10 Americans still listen to traditional radio each week, they are listening less. And the industry is having to confront many challenges like those that have enticed Mr. Costa, including streaming audio, podcasting, iPods and Howard Stern on satellite radio.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento